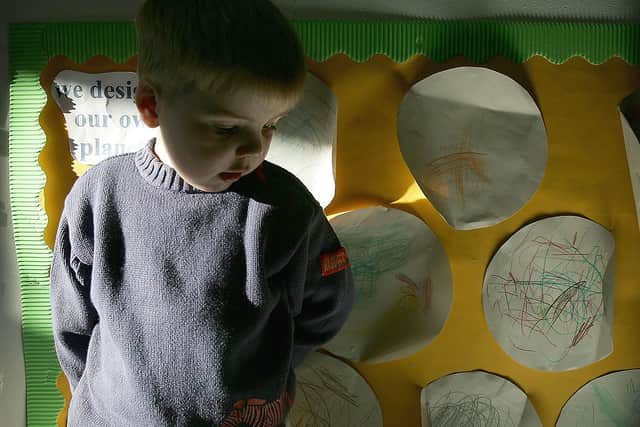

Children are still suffering ‘lasting’ impacts from Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns, experts warn

and live on Freeview channel 276

Children - particularly those under the age of 5 - are still suffering the “lasting” impacts of coronavirus lockdowns, experts have warned.

NationalWorld spoke to a series of psychologists, teachers, and early years specialists who revealed that the time spent in lockdown is still significantly hindering children’s development - with many missing key milestones, struggling with social and emotional intelligence, and suffering poor mental health.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was widespread concern at the height of Covid-19 about the sorts of repercussions that not going to school, daycare, or other activities would have on children in the short term - but the long-term effects have only really started to manifest in the past few months or so, more than three years after the pandemic first began.

Georgina Sturmer, a BACP registered counsellor, told NationalWorld she has seen a decline in general mental health and wellbeing among young people. “Teenagers are reporting more stress and anxiety,” she said, attributing it to them “absorbing messages that their world was unsafe”, and many have isolated themselves, either consciously or unconsciously.

“When children grow, they learn how to build relationships, how to socialise, how to seek support from families, schools, society. But during Covid, there was a real rupture in this type of connection,” Ms Sturmer explained. “Being alone may feel safer, and as they became used to interacting with their peers online, the online world might feel like a more familiar and less risky way to build connections.”

Sarah Melsom, a teacher in London, has also noticed a greater affiliation with the online world. “Teenagers are demonstrating an increased dependence on phones and screens,” she said. “There has also been a marked decline in focus in the classroom.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut while there is a need to address some of the new behavioural trends amongst older children - and particularly the decline in mental health and wellbeing - experts are currently more concerned about the potentially long-lasting impacts on younger children, whose development has slowed, stalled, or even reversed.

Michelle Mintz, an early development expert, said: “Studies show that 90% of brain development happens before a child is five years old.”

This means that for those born in the pandemic - or for those who were only one or two years old when lockdowns began - their most formative years, and their brains’ physical and emotional development, have been largely shaped by this experience.

Ms Mintz explained: “Research is showing that babies born during Covid-19 are falling behind on their milestones. During the pandemic, there were few to no opportunities for babies and toddlers to engage in social interactions, as well as minimal chances for conversation which has adversely impacted their talking and reading development.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We’re also seeing a reduced ability to recognise facial expressions, because of people wearing masks, and children being less able to vocalise their thoughts due to being isolated in their earlier years.” She added that this could create difficulties for these children as they get older, as they may struggle to “socialise with others” and experience “fewer feelings of comfort and trust around people”.

Ms Melsom echoed these concerns, pointing to the fact that more children are needing extra support with speech and language, while others are demonstrating difficulties when it comes to “social” skills such as sharing. Ms Sturmer added that amongst babies, there are noticeable delays in some of the fundamental development benchmarks, such as “pointing, waving, or saying words that are distinguishable”.

Neil Leitch, CEO of the Early Years Alliance, summarised the situation: “Children are arriving in early years settings at a point of development we are not used to. Essentially, they are behind where they should be.”

He too highlighted a deterioration in behaviour, admitting: “I’ve spoken to educators who are reporting staff being bitten and kicked by children. Why is this happening? Because children have not been socialised in the way they were before - at nurseries, toddler groups, parks, church halls.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMr Leitch warned that children struggling with socialising, whether that be sharing, taking turns, or understanding the needs of others, may start to demonstrate “withdrawal, selfishness, anxiety, and an unwillingness to participate.”

He continued: “Something else to note is that parents also weren’t receiving support in the same way. They weren’t able to get casual, day-to-day advice, to ask others, ‘how did you get them to stop doing this?’ And that’s not about parents being inadequate in the slightest - it’s about them also not receiving support.”

Mr Leitch said that these issues are being compounded by the fact that the early years sector is in a “crisis” - one which started long before Covid - facing severe staffing shortages, challenges with recruitment, and dealing with chronic underfunding.

“What this means,” he said, “is that when children arrive in our centres with additional needs - whether these be personal, social, emotional - we don’t have the staff we need to offer appropriate care, particularly urgently needed one-on-one support.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThings can be changed, however. “It’s never too late - but we need the investment from the government to fix things,” Mr Leitch insisted. “Currently, we spend money fixing problems instead of preventing them. Research shows that there are direct links between poor early years development and crime.

“If you get it wrong in the first five years, there is a strong chance that will carry through for the rest of a child’s life. So we have to view those under 5 as not just children who need childcare - we need to value the responsibility we all have to make sure our future doctors, teachers, and leaders have a good start in life.”

If the government ensures children can get the extra support they need post-pandemic, the experts argued, then they can be brought back up to speed. It’s not an “irreversible” problem.

A spokesperson for the Department for Education told NationalWorld: “The early years of a child’s life are so important, which is why we’re delivering a transformational package to support our youngest of children with their development.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Training is already under way for thousands of individuals through the Professional Development Programme, whilst 18 Stronger Practice Hubs are up and running across England. 90,000 children across two-thirds of primary schools are also benefitting from the Nuffield Early Language Intervention programme.

“With up to £180 million of funding committed up until March 2025, we remain committed to supporting early years professionals and helping children to recover from the impact of the pandemic.”

Outside of government intervention, there are also simple ways that parents and guardians can help reverse the impacts of the pandemic, according to Ms Mintz. For babies, she suggests prioritising visual stimulation - first with black and white objects before later transitioning onto colours - and moving things around faces to encourage making eye contact.

Plenty of talking, singing, and reading will expose babies’ brains to different hearing experiences, and introducing varying textures of objects - e.g. soft, bumpy, or rough - can support thir brains in learning to process different information.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor younger children, she advises encouraging them on how to communicate wants, thoughts, needs and ideas, and using plenty of facial expressions and body language when talking to help them understand social cues. Reading continues to be important, and opportunities to play and interact with other children is crucial.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.