At pains to maintain public morale in the early stages of war, British authorities quickly hushed up news of the RMS Oceanic’s wrecking after it ran aground off the coast of Foula, Shetland, on a calm September day in 1914.

The crew, later court-martialled for their poor navigation, were saved. The Oceanic, however, was swallowed whole into the Shaalds of Foula, becoming the Allies’ first passenger ship casualty before the navy could even put it to use.

For decades, the vessel - once the largest passenger ship in the world - lay undisturbed on the sea bed, shielded by geographical remoteness, infamously treacherous tides and a muted historical record. Then, in 1973, diver Alec Crawford became the first in 59 years to see it.

Through some combination of fortuity, perseverance and youthful recklessness, Alec and his diving partner rediscovered the Oceanic through a trial-and-error process of throwing an anchor from a boat until, one day, it stuck.

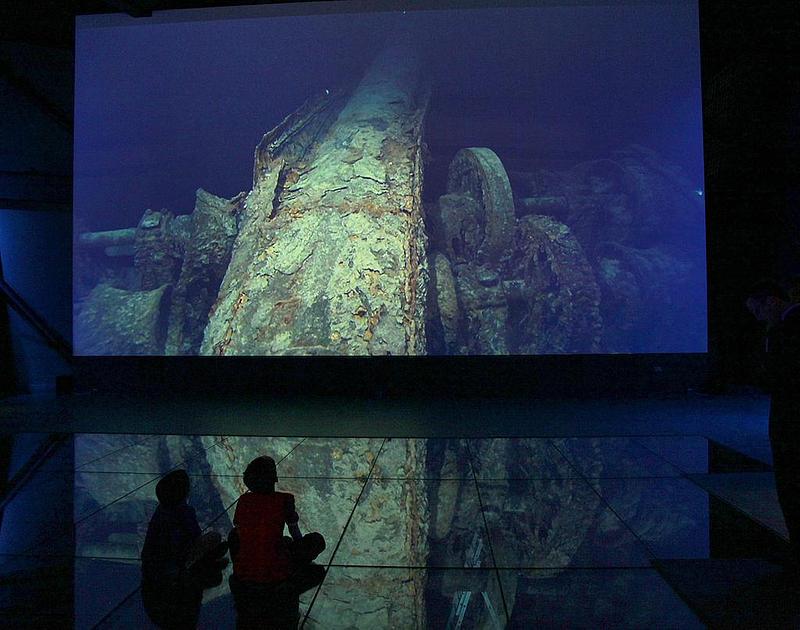

“The best way I can describe it is like going to a cathedral when it’s almost dark,” recalls Alec, of the moment he came face-to-face with the Oceanic’s colossal engines.

“The visibility wasn’t great so all I could see was the lines of it, and yet, there’s an awesomeness to it, like when you’re standing and looking up at a huge cathedral...you can hardly believe what you’re seeing...it’s almost frightening.”

Diving at the beginning of a boom in ocean exploration, Alec, who later wrote a book on his experiences, would not be the last to rediscover a long-forgotten wreck like the Oceanic; one of thousands that still lie scattered off almost every British coastline.

Best estimates, in fact, place the number of wrecks in UK territorial waters at around 40,000, before even mentioning the thousands more British wrecks abroad. Though finds have accelerated in recent years, the majority remain undiscovered.

Throughout most of history, these wrecks have been protected by oceans once impenetrable to humans beyond a few metres’ depth.

Over the past few decades, however, increasingly accessible and sophisticated underwater technology has sparked a new age of exploration, in which people - and man-made robots - are reaching depths previously thought impossible.

For archaeologists, this tech represents a world of opportunity, with unsurveyed wrecks a potential goldmine of information on cultures, people and ancient trade routes that could upend our understanding of human history.

With oceans increasingly accessible to all, however, it’s now a question of who gets there first.

From archaic legislation to “treasure hunting” companies in search of million-pound cargos, wrecks today face a myriad of threats which could limit their longevity for future generations. Without adequate protections, this irreplaceable record of Britain’s maritime history could be gone for good.

“These vast structures just disappear from sight”

The story of most human settlements is one of constant change: buildings are pulled down and rebuilt, roads are paved and new cities spring up from the ruins of old ones.

Shipwrecks, meanwhile, are what marine archaeologist Peter Campbell refers to as “a moment in time”. Providing a unique archaeological capsule of the day the vessel sunk, they are, he says, “perhaps the most valuable type of [archaeological] site”.

Depending on where, and how far down ships are located, they can be discovered in astonishingly pristine conditions, as with the 16th-century Baltic Mary Celeste, discovered in 2019 with guns still in firing position.

Dating from the Age of Discovery, the wreck gave archaeologists unprecedented access to the technologies available to Christopher Columbus on his 1492 journey to the New World.

Other wrecks, meanwhile, unlock information from even longer ago, with the 2010 discovery of a 3,000 year old Bronze age ship off the Devonshire coast suggesting European trade networks were thriving much earlier than previously thought.

“In Britain, you have watercraft dating all the way back to the Neolithic period”, explains Campbell, adding that such finds are the “main vector” for helping archaeologists understand “how people moved, traded and interacted with other cultures...these finds have revealed how well-connected people in Britain really were”

Beyond archaeologists, historic ships - and subsequent wrecks - have long been a subject of fascination among the wider public, many of whom grew up on tales of pirates, seafaring adventures, and, of course, treasure.

“People are endlessly fascinated by these vast structures just vanishing from sight”, says Alec, who recalls a large number of local people and fishermen coming to enquire about his wreck finds during his days as a diver.

It’s a fact perhaps no better demonstrated than by the ensuring cultural phenomenon of the Titanic, a wreck not only immortalised in the iconic 1997 film of the same name, but subject to incessant dives, auctions, arguments and ill-conceived plans - including one involving thousands of ping pong balls - to raise it from the sea bed.

In much the same way as tourists are drawn to the post-human landscape of Chernobyl, people are drawn to wrecks, too, as an eerie monument to disaster, completely frozen in time.

This human loss can be conflicting, says Glenn Gilbert, an amateur diver who has been visiting wrecks for almost a decade:

“Sometimes I do have a [guilty] conscience...I’m getting pleasure from being somewhere where I know people have lost their lives”, he explains.

“Seeing the artefacts people left behind can be very moving...but most divers are very respectful and just look, not touch”.

“The law gives a confusing message”

Not everyone, of course, treats cargo with such respect. In 2007, the wrecking of the MSC Napoli on Devon’s Branscombe Beach saw a swarm of people descend on the beach to swipe the cargo which had spilled from the ship’s containers - including a selection of pricey BMW bikes.

In the late 19th century, legend has it that the forebears of these scavengers once stood on South West beaches and used fake lights to deliberately misdirect ships to their demise, plundering the leftover cargo for profit.

While many have questioned the existence of fabled “wreckers”, the tales were, at the time, powerful enough to initiate cash rewards for saving the lives of wreck victims.

Financial rewards could also be reaped by reporting wreck finds to newly-appointed “receivers of wreck” stationed around the country.

Ever since then, “finders keepers” has been a non-starter when it comes to wrecks.

Like much British law today, the archaic legislation stuck, and though today the “Receiver of Wreck” (ROW) role belongs to one person alone, the same basic principle still applies: any artefacts or materials retrieved from a wreck must be reported to the ROW who will, in the first instance, endeavour to find its true owner.

If, after a year has passed, no owner has been found, the finder will either be allowed to keep the item salvaged or receive a cash reward in lieu - as items of historical importance may be passed on to museums or archaeologists.

In the 1970s, Alec and his diving partner turned a profit through this system, hauling up metals like bronze from wrecks, reporting them to the receiver, and selling them on - with a cut given to the ROW. It was a process that worked, says Alec, “extremely well”.

Today, wrecks within UK waters are protected by a plethora of laws which would make Alec’s old line of work nearly impossible to carry out, let alone make money from.

The most recent 2009 legislation, for instance, made it mandatory to obtain a license in order to lift wreck parts or artefacts, while most of the 62 “designated” wreck sites in the UK - exempting those in Scotland - are shut off to divers without explicit permissions.

There are loopholes and exceptions, however, with any items retrieved by hand - such as coins, bottles or plates - from an undesignated wreck not requiring licence permissions. Instead, finders simply have to report items to the ROW.

The endurance of this archaic ROW legislation alongside more modern laws, says says Dr Martin, makes the UK’s message on shipwrecks “confusing”; at once encouraging and discouraging people from salvaging historic wrecks:

“On the one hand we’re saying shipwrecks are important, we shouldn’t be interfering with them unless there’s a strong public interest...but then the historic salvage law gives the message that if you bring something up, as long as you report it to the ROW, you’re going to get paid an award for doing so.”

"These sites are ideal for criminals”

Such legislation is further undermined, says Dr Martin, by the UK’s lack of investment in underwater cultural heritage.

In a co-authored, 2019 paper on the weaknesses in Britain’s protection of such heritage, he points out that while Historic England’s 50,000 square-mile terrestrial remit has generated “a listing team of around 80 employees, a planning team of around 320 employees and around 136 researchers”, the 21,000 square miles of England’s territorial waters are looked after by just “two employees on the listing team and three on the planning team”.

This lack of investment limits the ability of archaeologists to survey wreck sites, in turn meaning little is known about what’s on wrecks - let alone what might have been taken from them.

“Until we know what’s down there, we can’t know what’s being lifted up”, explains Dr Martin.

Unlike in a museum or gallery, where artefacts and artworks are accounted for and heavily guarded, the majority of UK wrecks are thus totally unknown entities.

Steal a collection of ingots from a museum, and you’d soon find police knocking on your door. Steal them from a wreck, however, and you may just get away with it.

“In a horrible way, these [wreck] sites are ideal for criminals,” says Peter Campbell.

“There’s no record of these sites, so even if, say, 20,000 coins arrive on the black market, we might know they’ve taken them from somewhere, but it’s really hard to link them back to a specific [wreck] site.”

Robert Yorke, Chairman of the Joint Nautical Archaeological Policy Committee, further adds that such crime is almost impossible to detect unless the perpetrator is “caught in the act”, given the vastness of the oceans and the ability of vessels to “go black” by turning off their identification systems.

Paul Jefferey, Maritime Heritage Crime Advisor at Historic England, says that the ability of the body and the police “identifying crime and applying protections” has improved greatly in recent years, with “quite a few enforcement actions which have had a very positive deterrent effect [on looting]”.

He concedes, however, that small-scale looting from wrecks is a crime that’s “hard to quantify”, given the amount of unknown variables involved.

Both Dr Martin and Paul are quick to heap praise on the “respectful” diving community in general, with the latter pointing out that divers are “one of the most useful assets” English Heritage have in protecting wrecks around the country.

Dr Martin believes, however, that small-scale souvenir hunting “is still a big thing” among a minority, with “people who have garages full of stuff, who will openly admit to taking from wrecks”.

Finds reported to the ROW tell an incomplete picture, with the doubling of reported finds in 2020 (from 95 in 2019 to 224) perhaps indicating an increase in divers doing things by the book, or perhaps simply an increase in those out looking.

Past amnesties have given some clue as to the true scale of looting, with a three-month ROW amnesty on prosecutions in 2001 revealing 30,000 wreck artefacts that had not been reported by divers within the legally-required time frame.

Search hard enough on online diving forums today, and you’ll find whispers of sales to vintage shops and ancient coins stashed quietly in pockets.

The motivations for this kind of looting vary, says Yorke. Some will go on to attempt selling looted artefacts, while others - sometimes in ignorance of potential damage - are simply looking for a souvenir.

Regardless of intentions, says Campbell, the removal of even seemingly mundane artefacts can have a profound impact on archaeological work, disturbing materials around the item taken and erasing “critical information” such as dates on coins, which could reveal when the ship sailed.

Unnecessary removal of artefacts also negates the potential for future technologies to be deployed, says Campbell, pointing out that heavily-treated artefacts in today’s “shipwreck museums” can no longer be analysed using modern DNA techniques.

In other cases, removal of artefacts has simply led to their destruction, with Iona Murray, Deputy Head of Ancient Monuments at Historic Environment Scotland, recalling the impact of divers swiping historic telephones from Scotland’s famous Scapa Flow wreck site:

“These telephones were very early technology, with early electronics inside them. Once they were brought to the surface and exposed to air, the electronic components dissolved - all that technology was lost”.

“There’s nowhere to hide”

Others seem less concerned by the threat posed by amateur divers, with Robert Yorke, for instance, far more wary of professional “treasure-hunting” salvage companies, whose exploits he feels present the greatest threat to wreck longevity:

“The accessibility of [remote deep sea technology] - particularly for salvage companies - has increased the threat for wrecks dramatically,” he explains.

“Over the past 20 years, you’ve had all sorts of cases where vessels have been salvaged two or three miles down which in the past would have been completely safe. Now, there’s nowhere to hide.”

Reports of finds to the ROW in 2020 reveal a series of mundane, largely inconsequential finds likely retrieved by solo divers: bottles; pieces of metal; and in one somewhat eerie case, a collection of “porcelain dolls’ faces”. The odds are, in other words, stacked against the probability of finding valuable cargo on wrecks.

Yet like moths to a flame, salvage companies, treasure hunters and, most importantly for the hunters, investors, seem perpetually seduced by the prospect of sunken treasure. The damage they do to wrecks in the process, says Campbell, can be devastating.

Some take ruthless, illegal routes to profiteering, with a 2017 Guardian investigation revealing the wholesale plundering of British warships in Indonesia, with scavengers disturbing the human remains of soldiers to profit from metal on the wrecks.

Others, meanwhile, take a legal route, seeking financial investments for promised returns of millions in gold, silver and platinum cargos.

Salvage company Britannia’s Gold, for instance, claims to have located British warships carrying £300bn worth of gold bullion. At present, they’re seeking £5m more from investors, promising, in return, “the greatest ever gold recovery in history”.

Intending to bring their finds back to the UK, salvage companies like Britannia’s Gold are able to take advantage of the fact that many legislative protections of shipwrecks cease beyond 12 nautical miles from Britain’s shores; an area Campbell refers to as “the wild west”.

Campbell questions the profitability of large-scale treasure hunting ventures, suggesting there exists “a whole lot of people out there taking money from investors without even bothering to look for the wreck”. The costs of salvage, he explains, often outweigh the value of what’s discovered.

He points to one recent case in which a US treasure hunter “said he’d found a British naval vessel off Cape Cod, saying it was worth $3 billion because it was carrying a cargo of platinum”.

Nobody, including investors, says Campbell, bothered to look at the cargo manifest in Britain before handing over their cash. If they had, he explains “they would have seen the only cargo was tyres and car parts”.

Dr Martin, however, points out that treasure hunting ventures do occasionally strike gold - or silver, in the recent case of the SS Tilawa, in which bars worth a total of £32m were pulled from the wreck, deep in the Indian Ocean:

“Somebody lifted all that silver, brought it back to the Receiver of Wreck and they’ve been given title to it...under current (UK) law that’s perfectly legal”.

Cases like this cause controversy, says Dr Martin, not least because vessels like SS Tilawa are often war graves. In UK waters, many such ships are protected under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986; but the SS Tilawa was not in UK waters:

“There are several hundred people who died inside that ship [the SS Tilawa] and whose remains may still be there...yet someone’s gone in there are just hauled up the silver...this is heritage that belongs to everyone, it shouldn’t be open for taking”.

Such cases demonstrate, says Yorke, the absurdity of the 12 nautical mile limit at which UK protections effectively end. “The people who got wrecked,” he points out, “didn’t think about whether they were doing so at 12 nautical miles.”

“I’ve never seen a pristine wreck”

Many archaeologists also share a suspicion that commercial salvage pays no heed to the archaeological sensitivities of a wreck site; an assertion most salvage companies would furiously contest.

In a 2016 assessment on the impact of treasure hunting on wreck sites, UNESCO, in strong terms, asserted that “commercial exploitation operations regularly violate scientific standards of archaeological excavations”, given their “focus on the recovery of valuable materials”.

For such companies, greater access to the oceans has led to what UNESCO terms “the world’s greatest museum being broken into pieces”.

Without complete maps or inventories of what’s out there, it’s difficult to know the exact scale of damage, but Campbell’s own experience suggests it’s extensive and far-reaching:

“I’ve never seen a pristine wreck during my career, let’s put it that way”, he says.

It’s a situation Dr Martin fears won’t change until the government strengthens legislation and funnels more money into the protection and promotion of the UK’s rich portfolio of underwater cultural heritage.

The public, he adds, are fascinated by wrecks and other submerged heritage, but a sustained lack of investment in the sector means little is being done to maximise its potential:

“We’re not only not maximising it, we’re neglecting it and it’s causing difficulties for those of us who do want to get people engaged”.

What’s created is a vicious cycle, he explains, with a lack of funding leading to ignorance and disengagement, and thus less appetite for spending.

As a result, he adds, potentially important new wreck finds are often simply placed under an archaeological exclusion zone with no further plans for surveying what’s there - creating opportunities for theft.

And while the UK government has, in theory, committed to adopting - though have not ratified - the principles of the UNESCO convention on the protection of underwater cultural heritage, “they’re yet to put the principles into practice”, says Dr Martin.

Part of the issue, he adds, lies in the fact that cultural heritage is so often valued in economic terms, with officials reluctant to commit to the costs of shipwreck surveying and archaeology.

He points out that many governments - including the UK’s - have been historically driven by an interest in financial gains, going into partnerships with treasure hunting companies which have often ended in bitter legal battles over the spoils.

“The UK tends to treat heritage more as a business,” explains Dr Martin.

“Investing in [underwater cultural heritage] will cost money but it’s money that’s worth it because it engages the public, increases satisfaction and has cultural value”.

Soon, such questions around the protection and preservation of wrecks may become too pertinent to ignore, with an increase in off-shore development anticipated to uncover thousands more deep water vessels in the coming decades.

With the right investment, says Campbell, the financial and cultural benefits for Britain could be enormous, with new technologies opening up possibilities for national marine parks, VR dive trails and wholesale lifting of wrecks while still encased in sea water. In France, the country’s first underwater museum is already proving such ideas feasible.

On the flip side, however, further inaction could have the opposite effect, with opportunists seizing new technologies to exploit unprotected, undiscovered wrecks for personal or financial gain - snatching, says Dr Martin, “thousands of years of history” from the hands of the public.

“The UK has some of the richest waters for shipwrecks and thousands of wrecks around the world...those tell us about wars, international events and trading over thousands of years”, he asserts.

“While there’s some place for commerce in our approach, these wrecks and their cargos are nobody’s to lift and sell. Ultimately, this heritage belongs to every one of us.”

.jpg)