Driving from Europe to Africa - part one: crossing the Sahara from Morocco to Mauritania

Many people wondered why I wanted to drive from Italy to Senegal - I would struggle to provide reasons against the idea.

Having done the journey, I can now give an extensive list of reasons why driving from Italy to Senegal is a terrible idea: the risk of kidnap, disease, rife corruption and terrible, if any roads.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI was inspired by an Al Jazeera documentary about two Moroccan lorry drivers who drove from Agadir in the south of the country to Senegal’s capital Dakar. The majority of the film was close-up shots of the drivers complaining.

I wondered how difficult the trip could really be.

Having completely underestimated the risks and challenges of the 4,000 mile journey, I set off in mid May with my destination as the city of Ziguinchor in the troubled Casamance region of Southern Senegal.

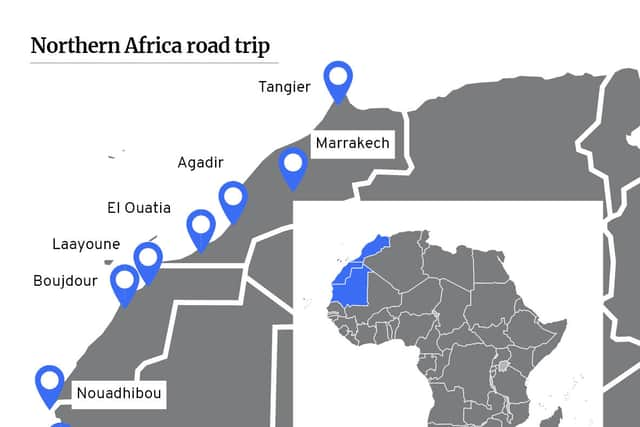

The beginning, and one third of the trip was an easy motorway drive to Algeciras in Southern Spain, where I boarded a ferry to Tangier in northern Morocco. From there it was another 500 miles south to Agadir, with a quick stopover in Marrakech.

Traversing Western Sahara

Following a night in a rather depressing seaside town called El Ouatia, I arrived in the region of Western Sahara.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWestern Sahara is a disputed territory. The subject of a deeply complicated conflict, it is located south of Morocco proper. Around 80% of the region is administered by the kingdom. The other 20% makes up the self proclaimed, partially recognised Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, situated in the eastern and southern parts of the territory.

I would be travelling through the Moroccan part on my journey, aside from a small but terrifying stretch crossing Sahrawi territory later in the trip.

Western Sahara is one of the most sparsely populated regions in the world, with the Moroccan and Sahrawi sides separated by a 1,700 mile long sand wall often referred to as the Berm.

On entering the city of Laayoune, the biggest town in Western Sahara and home to 40% of the territory’s population, I was stopped by local military police. When asked my profession I was perhaps foolishly honest and admitted I was a journalist.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe main officer who spoke good English brought me inside a roadside cabin and sat me down while he talked to his colleague on the phone. Throughout the process the officer was friendly and polite, having offered me food and water while I waited.

This kindness, hospitality and at least some level of English was consistent with officials throughout the plentiful and time-consuming police stops in Western Sahara.

After about 20 minutes of various phone calls, the man let me continue on my journey.

Further ahead and with the sun beginning to set I decided to spend the night in the town of Boujdour as I didn’t want to face the remote drive to the coastal city of Dakhla at night.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn entering the town I was subject to another wait at the police checkpoint. It was dark by the time I was allowed past and the officer who had stopped me organised a police escort to the local hotel.

I asked him if it was safe here - not knowing quite how to answer. He said yes while shaking his hand in a manner which suggested some doubt.

One thing I noted as I creeped further south was the occasional lone African man walking north along the road through the desert - Western Sahara has long been a transit point for people trying to reach Europe.

Some groups even attempt to reach EU territory by bypassing Morocco and the Mediterranean, embarking on lethal journeys from northern Mauritania to the Spanish Canary Islands, typically via a small, overloaded boat.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor the most part I enjoyed Morocco. The people were incredibly friendly, the food was good and the roads were all of excellent quality.

No man’s land

I wasn’t looking forward to Mauritania, my next destination.

The vast Islamic republic with a population of around 4.5 million, lies between Western Sahara and Senegal.

Slavery in the country, although officially abolished in 1981, is rampant and mainly revolves around a racial/caste system with the lighter skinned Arab elite enslaving the darker skinned Haratin and sub-saharan peoples.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 2018 it was estimated that 90,000 people in Mauritania (2.1% of the population) were living in slavery.

Atheism is punishable by death and as a result of the social structure that exists in Mauritania, poverty and inequality is immense.

I arrived at the border just before midday. The Moroccan complex was modern and well organised with professional staff - totally the opposite of the Mauritanian border.

Document checks over, I was allowed to leave Morocco.

The two nations are separated by a slither of land held by the Sahrawi republic which is described by people who regularly cross it as no man’s land - a perhaps accurate description as there are no formalities upon entering Sahrawi territory, no law enforcement or government. It truly is a lawless stretch of land.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGetting across this territory to reach the Mauritanian frontier post is therefore easier said than done.

The distance between Morocco and Mauritania is about two miles. Half of this is on a paved road. The other half is made up of nothing. There is no road, just desert which you are required to cross to reach Mauritania

Before even being able to move out of the Moroccan complex I was approached by a strange man who spoke very little English. He kept pestering me while the Moroccan guard carried out final checks on my documents. I attempted to ignore the man as I didn’t know who he was or could be.

The Moroccan border guard opened the exit gate of the complex. Stamped out of the country, I was sent out into the complete unknown.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUnfortunately for me, I seemed to be the only person crossing at the time, leaving me totally alone in no man’s land.

After the short-lived paved section lay a sort of wide inconsistent dirt track across the open desert, carved by the people who made the crossing before.

My car struggled getting over the sand, which in parts totally covered the path - occasionally the traction control light would begin flashing as the tyres spun.

I was now being chased by this strange man in his ancient Mercedes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPetrified of getting stuck, a potentially lethal mistake, my objective was to keep the momentum up. This was much to the detriment of my suspension as between the dunes were metre low dips in the ground and giant tyre shredding stones.

Yet I crossed as quickly as possible and finally arrived at the Mauritanian gates. Arriving in the country was like entering a lawless wild west.

Welcome to Mauritania

I was greeted by the intimidating Mauritanian border guards - all very young men, wearing green turbans and militia like outfits. They did not hesitate in opening the boot of my car and immediately helping themselves to my water.

One of the men grabbed my bag and took a particular interest in my laptop.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAn older guard as well as the the man who’d previously been chasing me intervened. Having gained my trust (not that I had a choice), the man led me to a building where I was given a visa upon payment of €55.

I was then led to the police station. Unlike any of the other travellers I was sat down and interviewed by a veteran police officer.

The polite officer wanted to know my itinerary, the hotels I would be staying in and my contact details, apparently for my own safety. Of course, this made me feel anything but safe.

Border formalities over, I was on my way to the closest city of Nouadhibou, where I planned to spend the night.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMoroccan Western Sahara and Mauritania seemed like different worlds to me.

The roads were significantly worse with immense potholes and moving sand dunes which would turn a two-way road into one-way. Road signs and road markings had completely disappeared.

Even the landscape was different. More depressing, as litter and car wrecks surrounded the roadside.

To get around the dune problem some sections of the road were elevated. However, there were no roadside crash barriers which meant if you skidded off the narrow, at times slippery road you could easily end up dead.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGone were the small modern French cars popular in Morocco and instead the only other vehicles would be ancient Mercedes sedans or more rarely giant modern Toyota land cruisers.

After only five minutes of driving in Mauritania I arrived at my first police checkpoint. I stopped my car and was slowly approached by an intimidating and angry looking sole police officer who didn’t speak a word of English.

I gave him my passport. Having stared at the visa for half a minute he then poked his head through the passenger side window and with a grin on his face made a money symbol with his hand. I had no local currency to pay him with. He then asked me via another gesture if I had a watch, which I did not. Eventually, he let me continue.

After a further two less corrupt checkpoints I arrived in Mauritania’s second largest city, Nouadhibou.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe differences between Morocco and Mauritania were even more pronounced in urban areas.

Every time I stopped my car, even for a few seconds, I would be surrounded by beggar children likely spotting my foreign number plate.

It was much more dirty, chaotic and noisy than Morocco. Every other car was severely damaged, while traffic lights and other road rules were completely ignored.

Religious chants from lamp post-mounted speakers were a consistent feature in the town - much louder and persistent than in other Islamic countries.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter settling into my hotel I began suffering from self doubt. As a skinny young white man in a small car and alone I’d be an easy target for any potential bandits. By the time I realised this it was already too late.

I wondered what would happen if my car broke down in the remote Mauritanian desert. In this part of the world there was no AA to call. If something went wrong my lack of any mechanical ability aside from a tyre change could be a recipe for disaster.

I decided to hire a guide to accompany me on the 425 mile journey south to the Senegalese border.

Having asked my hotel if they knew a local guide, which they didn’t, the hotel manager’s son offered to accompany me. Brahim, a chubby and surprisingly flamboyant 26-year-old, would come with me for the price of 15,000 Ouguiya (£330).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe left first thing in the morning on what would become the longest and most difficult day of my life.

Driving out of Nouadhibou before the sun had risen, the one-man ‘police’ checkpoints were even more frightening than before. The slow intimidating approaches by lone officers with militia-like outfits and face coverings in the dark certainly wasn’t comforting.

Fortunately Brahim did most of the talking.

An exhausting drive to Nouakchott

Given this was the deep Sahara, the drive south to Nouakchott was for the most part remote. However, we passed through one town which was home to a gold mine. Yet for a place where one of the world’s most valuable materials is mined, the town of Chami would struggle to be any more impoverished.

Local dwellings consisted of tiny shipping container-size huts and tents, all sparsely separated from each other. The main road through the town was lit by newly installed solar power lighting and filled with totally invisible giant speed bumps.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe stopped at Chami’s main petrol station to buy a few bottles of water. The forecourt had long been taken over by sand. The interior of the shop not only reeked of expired camel’s milk, it didn’t have shelves but instead open boxes from where customers could take produce.

People seemed hostile - perhaps angry to see a foreigner in their shop.

Next door was the local tea house. A man sat behind a plastic desk in this large boiling hot room, mainly taken up by prayer mats. On the desk were eight rows of noticeably filthy tea glasses - I didn’t fancy any.

Aside from the sand dunes and herds of camels often blocking them, the road to the south continued to get worse. Parts had horizontal mounds, sharp enough to instantly burst any car’s tyre.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFollowing seven hours and just after midday we arrived in Nouakchott, a city which was noticeably more wealthy and better developed than the rest of the country. Following a brief and shambolic petrol stop, we attempted to find the way from Nouakchott to Senegal.

Brahim had previously said he knew the exact route all the way to the border from Nouadhibou yet he failed to find a way out of the city. He decided to invite complete strangers into the car at separate intervals to direct us.

This entire episode was very bizarre, yet by this point in the day I had completely lost my sense of humour.

We travelled along the port road which acts as a sort of unofficial bypass. An area memorable for all the wrong reasons.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSmog completely blocked out any direct sunlight, while the smell of rotting fish became unbearable. Overloaded and truly ancient Mercedes ‘Kurzhauber’ lorries battled their way up the road, often with a few men on the roof.

I remember seeing one lorry in particular which was being driven with its wheels at an angle given its complete inability to drive in a straight line.

The road was totally barren. No street lighting or road signs - an exception being billboards promoting the Chinese government, notorious for meddling in Africa over the past few years.

A few metres away from the road were various industrial buildings. Not even directly connected to the road itself, these suspiciously well kept complexes were surrounded by high walls. Between the walls and road were shacks where presumably local workers lived in squalor.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne thought stuck in my head - this immense poverty and drastic change in environment was only a few days’ drive from Europe.

South of Nouakchott the landscape changed drastically, going from sandy desert to typical Sahelian shrub-land, with a noticeably higher density of towns and villages along the road from the capital to the Senegalese border.

This higher population also meant that the roads became much better, in part thanks to European funding as proclaimed on signs at the boundary of every village.

Villages in the south of the country seemed like they had been the target of some aid. It was easy to spot modern roadside wells, toilet facilities and even pedestrian crossings - the latter of which provided no beneficial purpose whatsoever given road rules in Mauritania are always ignored.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe entire day I felt extremely unwelcome, everything seemed very alien, I was exhausted and had been driving since 5:30 in the morning. I was also severely dehydrated. I had not drunk anything that day in an attempt to stop as little as possible.

My enjoyment of the trip had completely faded. It had become a stressful challenge which I wanted to end as quickly as possible.

Yet my real problems had not even begun. Within an hour I’d find myself a captive for ransom.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.