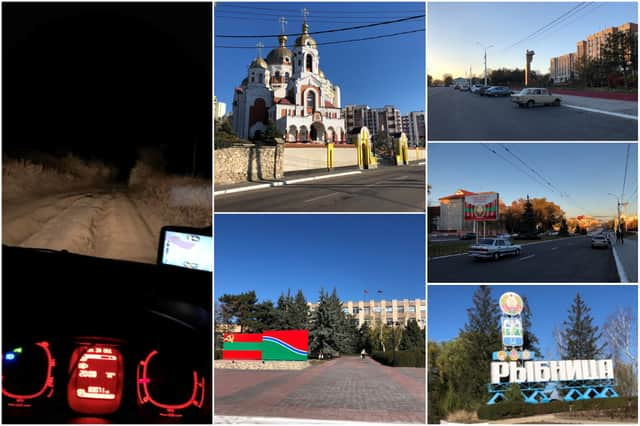

The country that doesn’t exist: taking a road trip to Transnistria

Transnistria is an unrecognised country few have heard of, which lies on the fringe of Europe.

The region is time warped in the Soviet era, as if the Iron Curtain was still in place, while only three other partially recognised post-Soviet states acknowledge the existence of the small nation. A short distance from its Eastern border preparations are being made for war in Ukraine.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe story of a road trip to Transnistria and beyond tells of chaotic border crossings, what must be Europe’s most extreme road works, Soviet style bureaucracy, a nation gearing up for war and a currency that has no value.

Starting the journey

My longest road trip to date took me through Transnistria, an unrecognised state in Eastern Europe where you would think the Soviet Union never fell and by the end of my journey I found myself waking up in a brothel hotel in the Ukrainian war zone.

I’ve always had a niche interest in the former Soviet space. Its size, its distinct uniform culture, the cookie cutter architecture, and as a petrol head, the vehicles. Quickly after learning about Transnistria (possibly the most post-Soviet place on the planet) I knew I would have to pay the region a visit.

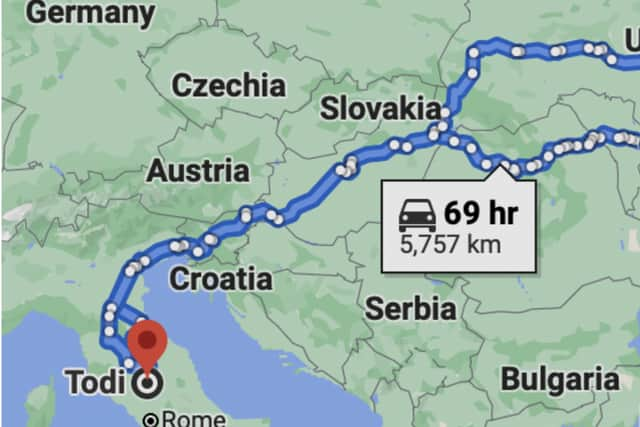

After a 900 mile, two-day motorway journey from Todi in central Italy, I had reached Romania.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAside from incredible scenery, the country’s lack of bypasses or motorways in combination with towns which seemed to revolve around only one road meant I spent a huge amount of time driving through urban areas on the trip from Satu Mare in the north-west to Iasi near the Moldovan border.

The Romanian style of driving led to two lane roads being turned into four lanes by the locals with many creative overtaking manoeuvres. If you ever drive through Romania you may notice many locals choose to decorate their cars in very large antennae - this is so they can communicate with each other to warn the presence of traffic police.

Exhausted, I arrived at the Moldovan border just as the sun was setting.

Spending around 45 minutes crossing the border, I was interrogated by intimidating guards, confused as to why I had come to Europe’s poorest country.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHaving eventually crossed the border I needed to buy a vignette and car insurance. I had to search around the border town of Sculeni to find a vignette as most petrol stations had sold out.

Olga, a completely charming elderly lady and the border insurance broker (and who by some miracle spoke Italian) was as baffled by my trip as the border guards. Pointing out some of Moldova’s crime issues she jokingly suggested I turn around.

Speeding through Moldova

Olga’s less-than-enthusiastic view of Moldova didn’t give me courage - I still had over 100 miles to drive to the hotel in Transnistria and it was dark…

Having got my insurance, vignette and water from the local shop, I headed on my way.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMoldova has a major problem with crime and corruption. The drugs trade is rife, human trafficking of woman and children is an issue and high level corruption is also present in the country. A bank fraud scandal in 2014 led to the equivalent of 12% of Moldova’s total GDP ($1 billion) vanishing from three of the country’s major banks. Police corruption has also historically been an issue.

Moldova’s murder rate is roughly three times higher than the UK’s at around four homicides per 100,000 people.

I felt unsafe driving through Moldova. There were few other vehicles on the roads, some of the ones that were had no number plates and there was a general feeling of lawlessness late at night.

Nonetheless, within ten minutes of leaving Sculeni I found myself at the top of a hill on a dirt road which my sat-nav had directed me down (TomTom clearly hasn’t got round to mapping Moldova). Realising that if I continued down it and got stuck I’d be a bit stuffed - I began reversing down the hill.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI started panicking when I saw two cars loitering at the bottom of the hill and increased my speed only to end up in a ditch.

Having got myself out of the ditch, slightly shaken and with a very sore neck, I got back on track. Sticking to the main roads, I more or less floored it all the way to the Transnistrian border.

En-route I stopped at a petrol station to check the underside of my car after the ditch incident - I noticed that the petrol station in Moldova appears to be the local equivalent to the pub (entire villages flock to the local garage for a drink or a smoke).

Where - and what - is Transnistria?

Transnistria is an unrecognised state sandwiched between Moldova and Ukraine. Officially a part of Moldova, it has its own government, currency, military, police, vehicle registration system and the main language is Russian.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, it is only recognised by three other partially recognised post-soviet states: Abkhazia, Artsakh and South Ossetia, whose flags are proudly flown in Transnistria’s capital’s main square.

Transnistria’s current status can be traced back to the disintegration of the Soviet Union when the region split from the Moldovian S.S.R in an aim to remain part of the Soviet Union in case Moldova were to unify with Romania. Soviet symbols are still widely used across the country and the original Moldovian S.S.R’s flag is identical to Transnistria’s current one.

Transnistria’s large ethnically Russian population is responsible for the state’s strong Russian identity with the region having previously asked to be annexed by Russia.

I felt intimidated by the barbed wire, souped up Russian military vehicles and soldiers in uniform at the highly militarised Transnistrian border. The design was more makeshift than other land borders, with pop-up shipping container buildings. The only two members of border staff were perfectly pleasant - I had to pay €8 for a vignette and my passport wasn’t stamped but instead I was given a flimsy paper migration card valid for five days.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter being allowed in, I drove straight to my hotel which I had to find by my rough memory of the city layout as neither my phone nor sat-nav worked here.

I spent my first day in Transnistria’s capital, Tiraspol.

My first task was to get the money I had brought with me changed into the local Transnistrian Rouble - foreign bank cards do not work on local cash machines.

Although similar to other major post-soviet cities, Tiraspol carries a certain uniqueness. The main boulevard is lined with patriotic billboards featuring the country’s crest and flag.

The flags of both Transnistria and Russia are proudly flown in places across the city centre and you’ll find war memorials featuring old Soviet tanks and planes across Tiraspol, while the roads are filled with classic Soviet vehicles.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe city centre features both extravagant Stalinist and some pre-revolutionary Russian architecture. There were also a few modern buildings similar to what you may find in Moscow, Nur-Sultan or Bakù with parts of the downtown area even having a relatively affluent feel to them.

The outer city is dominated by Kruschev and Breschnev era cookie cutter apartment buildings as well as some types of heavy industry.

The traffic was calm and the locals were forgiving when I was routinely holding everyone up in the wrong lane.

On my second day in Transnistria I drove from Tiraspol all the way to the state’s northernmost point near the border with Ukraine, via the the city of Rîbnița.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe main road across the country resembled one side of a British motorway - three lanes but with two way traffic. The condition of the road wasn’t bad but it was quite bumpy. Any lane would be used by a car going any way with some cars overtaking an overtaking car

The country is filled with old Soviet style mosaics, war memorials, and extravagant unique signs welcoming you to every town you pass which all remain in very good condition.

I found the people of Transnistria to be sincere, charming and curious as to why I had come to such a place - unfortunately my conversations were very limited thanks to my lack of Russian.

Having spent two full days in Transnistria, I packed up my things and headed to Ukraine.

A bumpy journey through Ukraine

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCrossing a country’s border in a car can be a draining task - guards are often very intimidating and you are usually treated with suspicion.

I was therefore relieved to find that entering Ukraine wasn’t what I expected with very cheerful guards keen to chat and find out where I was from and what I was doing - this warm welcome may have been due to Ukraine’s effort in boosting its tourism industry.

Relieved with the pleasant border crossing I arrived in Ukraine’s Odessa Oblast at around 10 in the morning. I’d planned to be in the North-Eastern city of Kharkiv that night - this would not be the case.

Within minutes of leaving the border I noticed that the road quality here was significantly worse than both Moldova and Transnistria. The roads were incredibly bumpy, filled with giant potholes and in some places, where lorries had gradually sunk their tyres into the surface, the road had little mountain-like formations on them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuring my travels it was impossible to forget that Ukraine was at war. I would regularly pass giant military convoys and often see military outposts on the side of the road.

By the time the sun had set I still had 50km to drive until I got to Kharkiv and the road quality kept on getting worse.

Possibly the biggest problem with driving in Ukraine is the roadworks.

This is something I discovered near the city of Melitopol, where I came across a man who was waving what looked like one side of a table tennis bat and a fire that had been lit next to the road - this is Ukraine’s equivalent of temporary traffic lights and instead of closing a few yards of one side of the road they’d closed around 15 miles of it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis meant I sat behind this red table tennis bat for over an hour watching convoys of vehicles coming the other way until a road-worker eventually flicked a switch on a single green light.

This setback crushed my dreams of reaching Kharkiv that night so I looked for the nearest hotel online. The only hotel I could find was nearly two hours away in the coastal city of Berdyansk, in the far east of Ukraine, around where the fighting is taking place.

After two hours of even worse roads than before I arrived at the overnight halt.

The receptionist was nowhere to be found but I did hear snoring coming from behind the front desk. I called a phone number which had been left on the desk and then - behind the snoring - I heard a phone ring. A middle aged man who wreaked of alcohol awoke and came to the desk.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMy room’s wallpaper was covered in glitter, there was a mirror above the bed and a single erotic picture on the wall giving me the impression this hotel was used by some of Berdyansk’s finer characters.

I woke up the next morning to find myself in a freezing cold room - there had been a power cut.

After a long, cold shower I headed out of Berdyansk.

Heading back west

By midday I had decided to head home and started the 1,800 mile trek back to Italy - it ended up taking me three full days just to get to the Hungarian border.

The next three days of driving across central Ukraine was certainly the adventure I had signed up for.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe following night’s hotel was also an experience - although not drunk, the very erratic accommodation manager appeared to be under the influence of something.

The completely bonkers roadworks also continued with a two-hour wait at another set of makeshift roadwork lights, and one section of roadworks in which they kept the road open while they were completely redoing it which made driving along it a sort of off-road course.

I also ended up having to take routine diversions as many roads had been closed including one in which a bridge had collapsed into the stream below.

These diversions were mostly not signposted and they would often close the only major road going in one direction for miles, so getting around them would be a nightmare. However, there was one signposted diversion which took buses, lorries and cars along the muddy backroads of a rural village.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDriving in Ukraine was immensely stressful and challenging, requiring a huge amount of patience, which I very much lacked.

My border crossing into Hungary was as chaotic as the previous few days’ driving. As I was handing over my documents to the Ukrainian authorities I was also being chased by a man from the tourism agency who was trying, in Ukrainian, to get me to fill out a survey about my trip.

After the document checking and survey filling I headed back to my car, only to discover I had somehow managed to lose my keys - my car was now sitting in-between the border between Hungary and Ukraine with queues of angry lorry drivers behind.

In a desperate attempt to find the keys I looked in the glovebox and thankfully found a spare set which I’d forgotten I’d left before I set off. After a thorough search of my car by the Hungarian authorities I was back on the Hungarian motorway network and my incredible week-long adventure had finally come to an end.

Overall I absolutely loved the trip. Both Ukraine and Transnistria are incredible places full of friendly and hospitable people - I’d highly recommend a visit if you ever get the chance.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.