We all have a responsibility to stop traumatising ourselves on social media

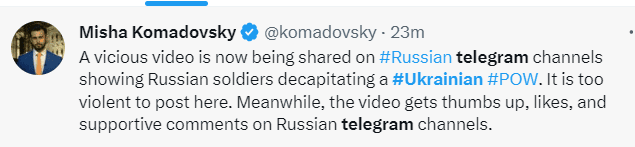

In recent horrific news from Ukraine, it has been reported that Russian soldiers apparently beheaded a Ukrainian prisoner of war lying on the ground. There has been outcry, and rightfully so, by foreign governments, condemning the atrocious video. Among them was President of the European Council, Charles Michel, who said: “Accountability and justice must prevail over terror and impunity. The EU will do all possible to ensure that.”

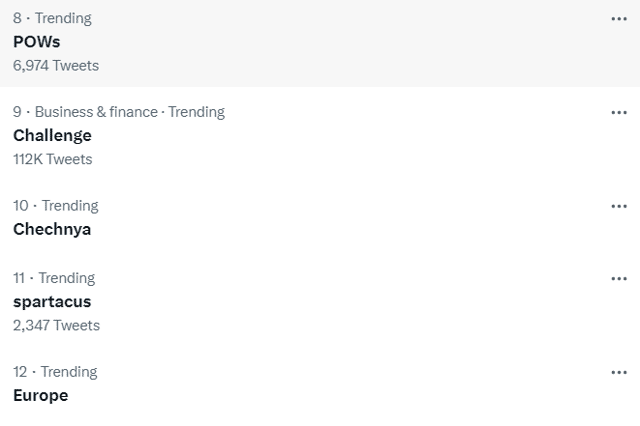

Whilst it is our work as journalists and analysts to look at and verify such terrible incidents, it takes a hideous toll. Despite the awful content of the video, it has been noted that people have been actively searching for the footage, with ‘POWs’ and ‘Telegram’ amongst the trending terms on Twitter (12 April).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe video has been widely circulated on encrypted messaging service Telegram - used by 34 million people in Russia, ranking second in the world for its usage of the network. What it shows is that while we all have a responsibility to treat our fellow humans with dignity, not everyone does.

Some people may fail to understand that even though these events may not directly affect them, second hand trauma is a reality for many in the field. This type of situation occurs when you experience the emotional and psychological effects of trauma by witnessing it through someone else's experience, such as a source or victim of a traumatic event. The Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, which started up as a project of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, says that second hand trauma or ‘vicarious trauma’ refers to “psychological changes resulting from cumulative, empathetic engagement with trauma survivors in a professional context”. The question is, if this is the effect, why would anyone seek out such a situation?

Fellow conflict journalist Oz Katerji pleaded with users this week to avoid watching the footage, saying “you have nothing to gain and everything to lose from staring into that abyss”.

As someone who spent years watching these kinds of images in a previous job as a news verification specialist monitoring real-time risks, from the murder of American journalist James Foley to the brutality of ISIS in Syria, I can say that it becomes engraved in your mind like a broken etch-a-sketch. Part of the work included watching some of the most terrifying images that make you question humanity, in order to flag it to the relevant authorities who could then act upon it. According to a 2015 study from the University of Toronto, extended exposure to disturbing material can have a severe effect on journalists’ mental health. And the public are not immune to this either, of course.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHaving access to these images at our fingertips is a double-edged sword. Not only have journalists been able to retrieve vital information from the ground within minutes, but governments are able to enact swift responses as a result. At the same time, violent images are permeating and shaping the daily lives of us all. As seen in the 2019 Christchurch attack, Meta, Twitter and Google only acted on 11% of anti-Muslim hatred reported to them despite the fact that the incident was livestreamed for 17 minutes on Facebook when it first occurred. How exactly is this helping your Average Joe? That’s the question Big Tech faces - even more so, the users actively consuming it.

After every major incident, there is always a plea from industry professionals as well as loved ones to not share images. But this tends to fall on deaf ears. After the 2017 Westminster attack for example, photos of the incident were quickly saved and reposted by individuals without context or warning. Visuals represent reality and condition our reactions to it. The more we share, search and indulge in violence for the sake of violence, the more we expose ourselves to accumulative stress for no apparent reason.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.