By and large, the street names in Bridlington, East Yorkshire, signpost a local history much like that of any other UK town. Priory Crescent, for a monastery established in 1133, Tudor Close, after the infamous English monarchs, and Tennyson Avenue, for the much-loved Victorian poet.

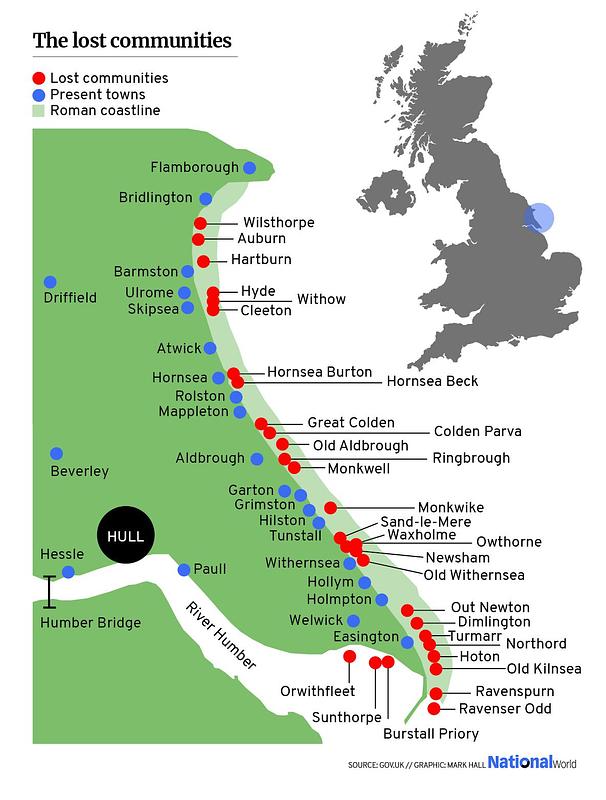

Venture away from the town centre, however, and you’d soon come upon a cluster of streets unique to this part of the country: Cleeton Way, Ravenspurn and Northorpe Rise.

These names might be unfamiliar to tourists, but to residents along Yorkshire’s east coast, they’re the stuff of local legend.

Ten miles down the road in Skipsea, it’s said that children from the village can hear the bells of Cleeton church pealing if they stand, straining their ears, on the cliff top at low tide.

If they strain their eyes, moreover, they’re promised a glimpse of the bell tower protruding from the waves, where the village of Cleeton - like Ravenspurn and Northorpe - was long ago swallowed by the sea.

“It probably works best on people with tinnitus,” jokes Andrew Walker, a local man who can trace his own ancestry in Skipsea back 300 years.

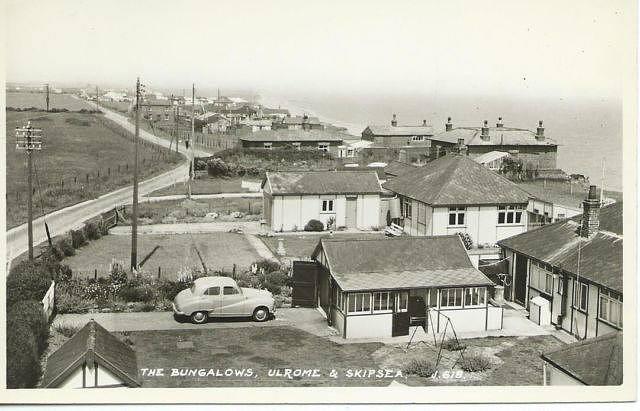

Like the generations before him, Andrew has spent a lifetime watching chunks of the village crumble into the sea thanks to the coastal erosion that’s been claiming entire settlements there since the last Ice Age. In his 48 years, he’s seen “a row of bungalows, a farmhouse and roads” go over.

Yet Andrew’s experience of erosion today differs from that of his ancestors in one important regard - a new era of extreme temperature change is speeding up the process.

Once upon a time, hard defences - like concrete sea walls - around Britain’s coasts were enough to hold back the tide. But as the country enters an age of extreme weather events and higher sea levels, it’s estimated that 114 miles of coastline are no longer cost-beneficial to protect from flooding, while around 1,000 miles are at risk of erosion.

Defenceless, and with climate change on their doorstep, dozens of communities like Skipsea now face being the UK’s first to be displaced by the crisis.

A canary in the coalmine for the UK’s battle with global warming, it’s cases like theirs which will test the limits of local and central government’s ability - and willingness - to prepare the public for seismic changes ahead.

A defenceless coast

'How many years before we should leave?'

It’s a scorching July day in Skipsea, and at the end of Hornsea Road, drivers periodically pull up, step outside their cars, then drive away after several minutes.

Some have made a Google Maps-aided error of thinking the road leads them directly to the beach. Most, however, have driven simply to peer over the jagged edge where the road has been sliced off by the sea.

Looking at the dramatic cliff-edge drop, and the sizeable cracks snaking their way through the remaining road, it’s not hard to understand the compulsion to stare. Even some locals, fearful of when the next storm might claim another chunk, regard the erosion with a grim fascination.

“I distinctly remember walking along what was Green Lane [in Skipsea] with my husband around 20 years ago,” recalls Alison Mitchell, landlady at the local pub, the Board Inn.

“When we moved here nine years ago, we were walking nearby and my husband pointed out that the place we’d walked was completely gone… that’s when it brought it to life for me.”

England and Wales’ coastline is today divided up into small units governed by one of four shoreline management plans (SMPs):

- ‘hold the line’, involving maintenance or upgrading of hard defences

- ‘advance the line’, involving new defences

- ‘managed realignment’, involving a shift to more natural defences

- ‘no active intervention’, meaning no defences are planned

Unlike some of its larger neighbours, Skipsea is governed by a “no active intervention” SMP, meaning coastal erosion has been allowed to proceed unhindered.

The policy has seen up to two metres of land lost every year, with a collection of houses now teetering on the cliff edge. In January 2020, more than 20 households - including those on Green Lane - were told that their homes were at “imminent risk” of collapse within 12 months. As of July 2021, only a thin strip of grass remains between them and the beach.

Though much of the UK coast is protected by sea defences, Skipsea is far from the only village at the mercy of the elements. Suffolk, West Sussex and swathes of Norfolk’s coast - most famously the village of Happisburgh - are eroding at a similarly alarming rate.

It’s thought that around 8,900 individual UK properties are at risk from coastal erosion, with 1,200 of those in areas, like Skipsea, without structural defences.

While the numbers might seem small in the grand scheme of things, victims of coastal erosion - unlike flooding victims - currently have no access to a national compensation programme should their homes be damaged or destroyed.

Though they have no statutory duty to do so, councils often award small grants for preemptive demolition of homes - a cost which would otherwise fall on the shoulders of the homeowner. In 2018, the Climate Change Committee (CCC) estimated that the number of properties affected will increase 15-fold by the end of the century.

This itself is a conservative calculation, with the UK’s complex geology and the unpredictability of landslides making damage hard to predict, while an absence of data on the number of buildings already lost further complicates calculations.

“I've seen parts [of land] which you think are at imminent risk of collapse, but five or six years later it’s still there - and other parts you weren’t expecting to go that just go overnight,” says Councillor Chris Matthews, who leads on environment and climate issues on the East Riding of Yorkshire Council.

In Skipsea, villagers have made their own calculations about when the sea will come lapping at their doors. In the main village, most believe they have hundreds of years but few are completely certain.

“We only bought our house from the council two years ago and we were actually thinking to ourselves recently - how many years before we should leave,” says Danielle Richardson, who lives with her family in Skipsea’s main village.

“We’re wondering if we should move to secure a future, financially, for our children because the closer the sea gets, the less the house will be worth.”

Even earlier than that, losing village fixtures like the holiday park could leave people jobless and struggling to remain in the area, explains John, a local man who agreed to give his first name only. Though some estimates give it longer, John believes the campsite on Skipsea’s cliffs “won’t be there in ten years”.

The threat of climate-related risks to UK communities hasn’t entirely escaped central government’s notice. In June 2020, a fresh flood and coastal erosion risk management statement promised a £5.2 billion investment in England’s flood and coastal defence programme over the coming six years, with the aim of protecting 336,000 further properties.

In a recent consultation on the nationwide ‘Flood Re’ compensation scheme for flood victims, however, respondents pointed out continuing disparities between flood and erosion risk communities.

“At present there are very limited initiatives such as Flood Re to assist and prepare coastal erosion (and permanent flood inundation) communities for a resilient future,” wrote one respondent.

Their concerns echo warnings made earlier this year by the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee (EFRA). The committee’s February 2021 flooding report claimed that the government’s statement lacks a “clear long-term objective” for flooding, having rejected implementation of a national standard to assess the resilience of defences.

This lack of target-setting, the EFRA Committee said, makes it unclear how far the government is prepared to go to protect flood and erosion victims.

“The Government needs to be frank about the level of risk it is prepared to accept in extreme climate change scenarios, and those likely to be affected need to know now,” read the report.

The limits of protection

'Plans to adapt are needed now'

“How far are they willing to let it go? Because it will come all the way into the village if they let it,” says John, who’s lived and worked in Skipsea for six years.

This question of ambition is one that’s long been on the lips of residents.

Like many of his neighbours, John feels that Skipsea has been forgotten about by those with the power to act, pointing out that “everybody pays their council tax here - we should all get a fair hearing”.

“I have a funny feeling that had we been down south, in Kent or somewhere, they’d have done something about it,” he adds.

Though authorities often use gentler terms to describe the algorithms used for decision-making on defence building, John’s analysis is close to the mark - large, built-up areas gain protection, while smaller, dispersed communities lose out.

Much of the process comes down to cost-benefit analysis, says Mike Elliott, Professor of Estuarine and Coastal Sciences at the University of Hull.

“They [decision-makers] have to make difficult choices just because of the sheer cost of protection… often the costs of moving would still be less than building a defence.”

What’s more, defences on one part of the coast risk offloading sediment south, quickening erosion in other areas, he explains.

“The first question is, could you stop it… but the next question is should you stop it? Because the sediment that comes off the cliffs just moves down the coast.”

Shoreline management plans for each unit of coast must assess which option is most sustainable in the short term (0-20 years) all the way up to long-term (50-100 years), with policies sometimes changing between these time frames.

Many, however, have failed to keep up with the accelerating pace of climate change, with the costs of implementing current policies projected to cost £18-£30 billion up to the end of the century. For at least 149 to 185 kilometres of coastline, the CCC has estimated the cost outweighs the benefits.

This means that even areas behind coastal defences - under ‘hold the line’ policies - may struggle to qualify for hard defence funding in the future. Should these defences be abruptly removed, an accelerated rate of erosion is likely.

Local councils face limited options in areas where erosion can no longer be held back - though Cllr Matthews said that he dislikes the term “no active intervention” for its implication that the council “are doing nothing to help”.

In areas like Skipsea, where defences are deemed unviable, the council monitors erosion closely and “works with residents to help them to adapt to the changes and risks they face” through “limited financial assistance and free advice”, a council spokesperson tells me.

Yet to locals, a lack of defences can look much like a lack of action.

“I don't think the government or the council or the people who are in charge of it all are doing enough,” says John, who questions why the neighbouring village of Mappleton is defended while Skipsea is not.

Alison calls the response “reactive, not proactive”, with the council simply demolishing homes on an ad-hoc basis, while the remainder of the village feel left in the dark about their collective futures.

Each time Skipsea’s cliff top homes hit the headlines, says Andrew Harland, another local to the area, “the reports are all much the same and the inferred conclusion seems to be; ‘something must be done! But nothing can be done!'”

Part of the issue lies in the fact that while funding is available for hard defences, “there’s no such equivalent for funding an adaption programme”, says Dr Sophie Day, an expert in coastal change at the University of East Anglia.

This means that where hard defences aren’t viable, there’s little middle ground available, with councils “having to think innovatively” to fund adaptive measures such as demolition, rehoming and relocation of businesses, she says.

So ad-hoc is the funding, in fact, that EFRA were told earlier this year that the East Riding Council were forced to approach the EU for money in absence of help from the UK.

“Realistic plans to adapt to the inevitability of change are needed now”, the CCC urged in their 2018 report. Three years on, however, and coastal communities remain in limbo, uninformed and uncertain about what comes next.

Disappearing daily

It’s literally disappearing every day'

It’s not just coastal change; in the CCC’s 2021 Progress Report to Parliament, the committee warned of a lack of adaptive measures across all areas of climate risk, stressing that many changes to the climate are now locked in up to 2050 - and the UK needs to be ready.

The report also said that the planning system is failing to take account of long-term coastal erosion projections, with developers continuing to build behind defences they assume will be maintained for decades to come.

Local governments have limited devolved powers to act in line with climate targets such as Net Zero, meaning the need for housing often takes precedence over climate risks, the report said.

Failure to plan adequately for future coastal change won’t just have negative economic consequences, but knock-on impacts for the mental wellbeing of those affected - who face losing not just their home, but sometimes their entire community.

Erosion has already begun to take its toll on the people of Skipsea, with Danielle pointing out that many of the homes on Green Lane are “in a state of disrepair - they feel there’s no point doing anything to them”.

There’s a sense among locals that the battle is already over, says Alison, with pleas for further action long unheeded.

“It might come across that the residents of Skipsea feel a bit defeated or beaten… but until now there doesn’t seem to have been anything positive about trying to make things better.”

“The road from Ulrome to Skipsea has completely disappeared. If that didn’t change anything then what would?” she adds.

With coastal communities often more vulnerable in socioeconomic terms than those inland, the issue of mental wellbeing is likely to be further compounded by a limited capacity to prepare for and recover from damage and flooding.

“There are lots of people who have got nothing apart from the four walls they live in, so you can imagine the anxiety and fear,” Dr Day says.

“The mental health issues around this are really substantial - you’re living in a state of uncertainty and fear about the future.”

We owe it to those at risk, says Dr Day, to prepare early, and involve communities in the process of decision-making.

“It’s about looking after people’s sense of place and identity - looking at how you might enable a village to continue in a slightly different format.”

Some might argue that in Skipsea, a key part of the village's identity is already ebbing away. In spite of being a traditional seaside resort, it’s in the position of having no safe access to the beach, with only a rope slung over the cliff offering a way down for the brave or agile.

To locals like Danielle, access to the beach is “the least they could do” as a gesture to Skipsea residents that they haven’t been forgotten.

An East Riding council spokesperson said that the “technical difficulty and cost of installing safe, sustainable access” means they currently have no plans to do so.

In many areas of government, decision-makers continue to shy away from investing in adaptive measures for coastal change.

Sometimes the reason is as simple as cost, but such hesitancy may also be down to adaptive measures - like relocation and demolition - being far more politically sensitive than the immediately visible solution of hard defences.

“Facing up to inevitable change requires difficult decisions. Coastal communities need to be engaged to plan for their future over several decades, but the capacity and political will to do so does not currently exist,” the CCC warned in 2018.

Re-evaluating the risks in 2021, their assessment found that little has changed, with “decisions [around erosion] being pushed into the future rather than addressed now, despite the increased consequences from climate change and rising sea levels.”

In Skipsea, the outlook remains pessimistic, with locals fearing their ongoing predicament is too easy for the headline-driven 24-hour news cycle, and the politicians responding to it, to ignore.

“Climate change in a city is pollution incidents, bad weather. When climate change is reported on national news it’s because of a heatwave or flash flooding,” says Alison.

“While that’s terrible, those events happen once or twice a year. In Skipsea, climate change is happening all the time. It’s literally disappearing every day.”

Even those some way from the cliffs, says Andrew Walker, “live under a cloud”, knowing that the sea will eventually force its way inland.

“Unless the government does something to protect us we’ll just become another village to be taken by the sea.”

More from NationalWorld

- Read more coverage of the environment and climate crisis on NationalWorld.com

- Follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram

- Sign up to our daily newsletter