Gulf Stream could collapse from 2025 causing ‘severe’ climate impacts with world ‘unable to cope’, study warns

and live on Freeview channel 276

The Gulf Stream could collapse as early as 2025 under the current scenario of future emissions which will cause “severe impacts” with land and marine ecosystems “unable to cope”, a new study has warned.

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (Amoc), the formal name for the Gulf Stream, has already been known to be at its weakest in 1,600 years due to global heating but now scientists say they have 95% confidence it could collapse between 2025 and 2095.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe study, published in the journal Nature Communications, gave a central estimate of 2050 if global carbon emissions are not reduced and the collapse is of “major concern” as global temperatures continue to rise.

The Amoc continued to collapse and restart repeatedly in the cycle of ice ages that occurred from 115,000 to 12,000 years ago, and researchers have spotted warning signs of a tipping point in 2021.

The new study used sea surface temperature data dating back to 1870 as a proxy for the change in the strength of Amoc currents over time.

The researchers then mapped this data onto the path seen in systems that are approaching a particular type of tipping point called a “saddle-node bifurcation”, then extrapolated the data to estimate when the tipping point was likely to occur.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe results are based on whether greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise as they have done to date. If emissions start to fall then the world would have more time to try to keep global temperature below the Amoc tipping point.

The researchers said the results “are under the assumption that the model is approximately correct, and we, of course, cannot rule out that other mechanisms are at play, and thus, the uncertainty is larger.”

They said: “However, we have reduced the analysis to have as few and sound assumptions as possible, and given the importance of the AMOC for the climate system, we ought not to ignore such clear indicators of an imminent collapse.”

The researchers added that the results are “worrisome” and “call for fast and effective measures to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe study comes into sharp contrast with the most recent assessment by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) which concluded that Amoc would not collapse this century.

Scientists have also questioned the new study as it “neglects factors” and the climate impacts of a collapse could be “less dramatic”.

Professor Andrew Watson FRS, Royal Society Research Professor at the Global Systems Institute, University of Exeter, said: “While their tipping point analysis is robust and suggests the system is approaching a transition, it doesn’t give a clue as to what lies beyond the transition. I’m unconvinced that this would be a catastrophic collapse.

“The instability could be less dramatic, not a full-scale shutdown but a change in the sites of deep water formation for example.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Ben Booth, senior climate scientist at the Met Office Hadley Centre, said other factors “such as volcanic and industrial aerosols” also “project onto the same historical records that this study uses as purely a fingerprint for past historical change in overturning.”

He added: “This new study neglects these factors, so a lot of caution needs to be taken in interpreting the findings as a definitive inference of the future overturning change.”

Professor Penny Holliday, head of marine physics and ocean circulation at the National Oceanography Centre, and Principal Investigator for OSNAP, detailed what would be the “severe impacts” if the Gulf Stream was “switched off”.

She said that after a “few decades” there would be “much lower surface temperatures and stronger winds across the whole northern hemisphere (land and ocean)”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdProfessor Holliday said major rainfall zones would shift leading to far less rainfall over Europe, North and Central America, north and central Africa and Asia, and more over the Amazon, Australia and southern Africa.

Sea ice would extend southwards from the Arctic into the subpolar North Atlantic, and the Antarctic sea ice would extend northwards.

She said for people and governments this would lead to “dramatic change in every nation’s ability to provide enough food and water for its population.”

She added: “Energy supply and demand would change rapidly with new climate conditions and infrastructures would need heavy investment to adapt and cope. The patterns of vector-borne disease and health (including mental health) would be profoundly affected.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“World-wide many land and marine ecosystems would be unable to cope and adapt to such fast changing climate conditions and biodiversity would be severely impacted.”

What is the Gulf Stream and how does it work?

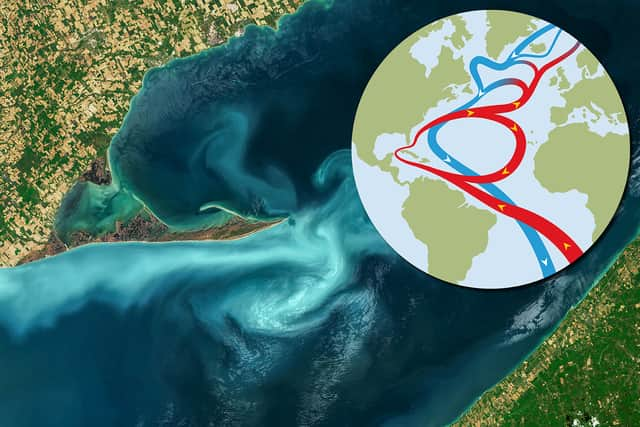

The Gulf Stream originates at the tip of Florida, and is a warm and swift Atlantic Ocean current that follows the eastern coastline of the US and Canada before crossing the Atlantic Ocean towards Europe.

It is one of the strongest ocean currents in the world and it ensures that the climate of Western Europe is much warmer than it would otherwise be.

It brings warmth to the UK and north-west Europe and is the reason we experience mild winters.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Gulf Stream works by warm water flowing from the equator to the poles, cooling down during this process with some evaporation occurring which increases the amount of salt.

Low temperature and a high salt content means high density and the water sinks deep in the oceans, moving slowly.

It eventually gets pulled back to the surface and warms in a process called “upwelling” and the circulation is complete, according to the Met Office.

The global process makes sure that the world’s oceans are continually mixed and that heat and energy are distributed to all parts of the earth, contributing to the climate we experience today.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.