Sanctions on Russia: have UK, US, EU restrictions worked on Ukraine war anniversary?

This article contains affiliate links. We may earn a small commission on items purchased through this article, but that does not affect our editorial judgement.

and live on Freeview channel 276

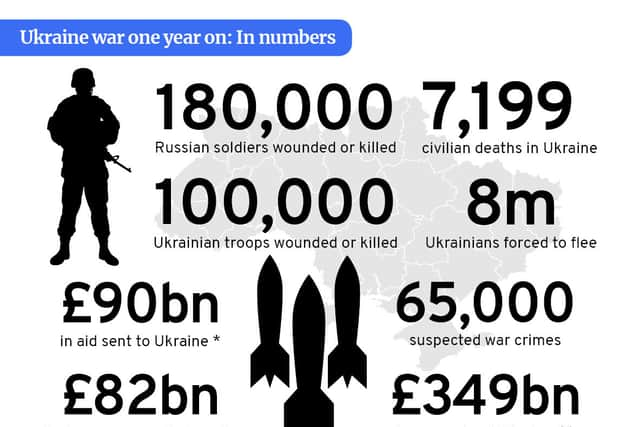

Ruined tower blocks, shrapnel-riddled walls, piles of rubble that used to be homes, schools and workplaces. These are just some of the physical consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine a year ago.

But Vladimir Putin’s decision to send troops into Russia’s western neighbour has left his country’s international reputation in tatters. It has also arguably firmed up the military and economic bonds between European nations, as well as those they share with the US.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough their decision to stand against the Kremlin has cost their economies dearly - much of the inflationary pressure behind the cost of living crisis can be traced back to the Russia-Ukraine war’s impact on energy bills, fuel costs and food prices - the western alliance appears to be holding firm, for now at least.

At the same time as a hot war has raged in Ukraine, a new cold war has emerged elsewhere. The West has fought Russia with sanctions rather than bullets (although it has supplied arms to Ukraine, of course).

So what has the impact been on Russia’s economy - have sanctions worked?

What sanctions have been imposed on Russia?

According to James Nixey, director of the Russia and Eurasia programme at foreign policy think tank Chatham House, the strength and breadth of the sanctions implemented against Russia were “more than Moscow had expected”. Indeed, an oral history of the lead up to the conflict that has been compiled by Politico has revealed the US and its allies spent several months carefully planning them.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe West has basically sought to cast Russia out of the global financial system, and cut its ties to international trade. It has imposed price caps on Russian oil and diesel (key exports for Moscow that generate billions of dollars for the Kremlin), frozen Russian Central Bank funds and restricted access to SWIFT, the dominant system for global financial transactions.

Around 2,500 Russian businesses, government officials, oligarchs and their families have been targeted by sanctions. These measures are depriving them of access to US bank accounts, UK property and financial markets.

On the flipside, the UK has barred individuals and companies from acquiring land or other assets in Russia. It has also stopped luxury goods from entering the country.

However, there have been loopholes in the packages that have allowed money to continue to flow into Vladimir Putin’s coffers. Climate change group Global Witness has found Russian oil is still flowing westwards, for example - something Ukrainian officials have also reported, and have urged the West to act on.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMeanwhile, subsidiaries of Russian companies have been able to exploit gaps in the UK’s visa system. It has allowed people linked to the Kremlin to enter the UK.

To mark the anniversary of the conflict, the White House and G7 have unveiled another tranche of sanctions. Russia’s metals and mining sector has been targeted, with further financial blocks having been put into action on Russian banks, arms dealers, tech companies and 250 individuals. The West has also targeted alleged sanctions evaders in countries like the UAE and Switzerland.

As well as state-level sanctions, major companies including McDonald’s and Apple have either ceased or dramatically reduced their operations in Russia.

Have Russian sanctions worked?

If the intention was to hobble Russia’s economy to the extent that it cannot afford to fund its war machine in Ukraine, the sanctions have failed. But Western powers have set targets that give them the wiggle room to argue that their sanctions packages have been successful.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnnouncing the latest package of sanctions, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said the effect of the West’s actions had been “seen acutely in Russia’s struggle to replenish its weapons and in its isolated economy”. The EU has said its involvement has been intended to impart “severe consequences” on Russia for its invasion, and to “effectively thwart” Russia’s abilities to continue to wage its war.

While Russia has indeed struggled to afford the firepower it needs to deal any decisive blows against Ukraine, its economy remains afloat - partly thanks to the surge in global oil and gas prices in the wake of its invasion of Ukraine. Its revenues from its vast fossil fuel resources grew 28% in 2022 - although it has now lost almost its entire European customer base and is struggling to find takers in other parts of the world.

Chatham House reckons the sanctions will ultimately land a “chronic blow” to Russia’s economy, but that this has not yet been fully realised. Part of the reason for this, according to US journal Foreign Affairs, is that the Kremlin prepared itself for a war by building up “substantial financial reserves”, boosting trade links with Asia, and suppressing freedom of speech at home.

It has also masked the true effect of the war on its economy by fudging its data - claiming unemployment is lower than it actually is, propping up the ruble so its price remains elevated, and reporting only a 3% contraction in GDP (despite its GDP including the production of military equipment that has gone on to be destroyed by the Ukrainian military).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

But it will only be able to paint this misleading picture for so long. A US congressional research document states that “economic conditions in Russia are starting to deteriorate at a faster rate”. It based this assessment off Russian central bank forecasts that the country’s economy would contract rapidly towards the end of 2022. Even if President Putin’s regime achieves some future successes in its war on Ukraine, the long-term economic prognosis looks bleak for his citizens.

With the West now ramping up the sanctions, 2023 could well become the year of Russia’s economic collapse. But the financial chaos predicted by some in the wake of the first waves of sanctions has thus far not come to pass, so the country could yet defy expectations.

And the longer it takes for these sanctions to truly bite, the greater the destruction and death toll on the ground in Ukraine.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.