Severance review: Apple TV+’s touching sci-fi satire rejects a crushing corporate world

and live on Freeview channel 276

There’s a really clever science fiction idea at the heart of Severance. The procedure that gives the Apple TV+ show its name acts like a sort of mental partition: employees at Lumon Industries have their memories bifurcated, unable to remember their home life when they’re at work and their work life when they’re at home. Mark Scout (Adam Scott) enters the elevator, full of regrets and anxieties and grieving for his wife; Mark S exits the elevator, no recollection of who he is the other 16 hours of the day, allowed no tangible connection to the outside, not even a surname.

Immediately, Severance announces itself as a sort of corporate satire – it’s the idea of a work/life balance twisted and taken to extremes. There’s a lot of it that’s thematically reminiscent of other works, from Philip K Dick short stories to episodes of Black Mirror, and its plasticky 1980s business aesthetic has cropped up in recent years in Doctor Who, Loki, and The Good Place amongst others; it’ll feel familiar even if you can’t rattle off a list of influences and contemporaries, though. Rarely does that familiarity feel like a problem, though, and indeed it’s often easy to forget – Severance is very much a case of “if you can’t be the first, then be the best” in action.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

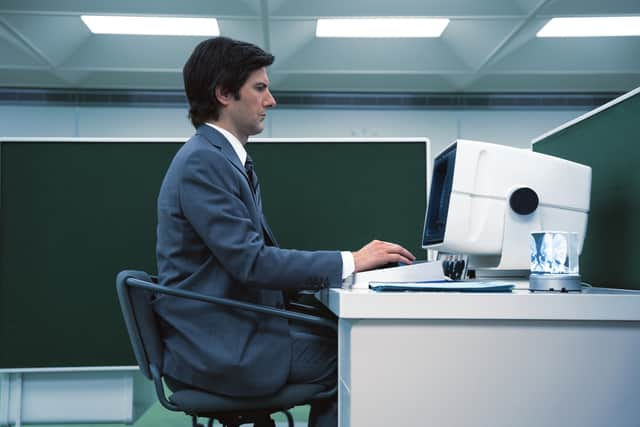

Hide AdPart of that is just down to how well executed the whole thing is. Directors Ben Stiller and Aoife McCardle evoke that queasy corporate banality with great skill; the whole series looks slick and stylish, making those off-white offices and cramped cubicles at once visually impressive and deeply offputting. The direction is very mannered, very precise; Stiller and McCardle convey this sense of control, palpable in the way the series is staged and shot (and, more subtly, the contrast in the colour grading between the inside and outside worlds). It’s the directorial equivalent of a senior manager with a fake smile that doesn’t reach their eyes and a firm hand on your shoulder, insisting they’re a friend while reminding you exactly who’s in charge.

You get the sense of Lumon Industries as a sort of strange, liminal space, combining the sensibilities of an unknowably vast corporation and a fundamentally very myopic way to live. For the workers (the “innies”, as they’re called, in contrast to the “outies” who have a life beyond the four walls of the Macro Data Refinement office) Lumon Industries is all they ever know. Weekends, sick days, and just going home for the evening is akin to blinking, with no lasting reprieve from the work on offer. They speculate about their outside lives, sometimes, but rarely, and all they really have to look forward to are cloying, “fun” corporate rewards for reaching quarterly targets.

What’s striking about Severance, then, is how invested it is in interrogating how that sort of life would affect someone – and who would choose it in the first place. The Macro Data Refinement (sorting “scary” numbers from “happy” ones – the work they do at Lumon Industries is oblique, and each new detail revealed only makes it feel even more out of reach) office is made up of four people: newly-promoted Mark S (Adam Scott), dedicated company man Irving B (John Turturro), waffle party devotee Dylan G (Zach Cherry), and recent hire Helly R (Britt Lower). Helly’s induction begins the series – she doesn’t know who she is or where they are, she doesn’t remember her childhood or the colour of her mother’s eyes, or even her own name. She’s also determined to escape, sneaking out of fire exits and trying to write messages and communicate with her other self. Each time, though, her “outie” returns, never moved by her “innie’s” plight – from a certain point of view, after all, Severance is quite an attractive procedure, a way to avoid any conscious experience of working. Or for one of them at least, anyway.

To the employees, their other selves are completely unknowable – there’s no way to tell if, on the outside, they’re kind and compassionate or cold and capricious, if they have a family or if they’re completely alone. Mark S arrives at the office with red eyes: does he have hayfever, or was he weeping on the way to work? Lumon Industries offers “wellness checks”, where employees can learn scant details about their other lives, but they amount to little more than vague platitudes: “Your outie likes films, and owns a machine that can play them”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the absence of their own history, they’re offered Lumon Industries history: the biography of founder Keir Eagan and his nine principles laid out in the company handbook. There’s a quasi-religious, paternalistic feel to it, pitching Eagan as something akin to a Robert Owen/David Dale-esque factory owner; it’s the closest thing the employees have to a shared frame of reference or any kind of identity, though, and seeing them gradually lose faith in it is strangely heartbreaking in its own way. That question of meaning, lost and found elsewhere, is what drives the series – in amongst the high-concept satire is this quietly very touching story of the MDR department building fleeting connections into something more.

It’s all brought to life by strong performances across the board, and it’s hard to pick any particular standout without immediately wanting to change your mind. Maybe John Turturro’s sweet bond with Christopher Walken – or, no Tramell Tillman’s perfect physicality as Mr Milchick – wait, actually, the subtle nuances to Adam Scott’s two performances, the only character we follow in both guises – or maybe Zach Cherry in episode 7 – but, wait, what about everything and anything Britt Lower does. So on and so forth, really: they’re that good.

Ultimately, then, Severance isn’t just one of the smartest new dramas of the year, but one of the most affecting too: it takes that familiar corporate world and renders it with such detail and such heart that, much like the severed employees, you won’t be able to tear yourself away. Unlike them, though, you won’t want to either.

Severance begins on Apple TV+ on Friday 18 February. I’ve seen all nine episodes before writing this review.

A message from the editor:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThank you for reading. NationalWorld is a new national news brand, produced by a team of journalists, editors, video producers and designers who live and work across the UK. Find out more about who’s who in the team, and our editorial values. We want to start a community among our readers, so please follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and keep the conversation going. You can also sign up to our email newsletters and get a curated selection of our best reads to your inbox every day.

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.